Why releasing trauma causes a loss of identity

- 7 June 2023

- Posted by: Michael H Hallett

- Category: Generational trauma ,

Releasing trauma is a process. As a process it undergoes identifiable and repeatable stages. The phrase ‘releasing trauma’ can be understood as referring to the overall process, as well as to the stage within the process when we bring the incomplete (traumatic) experience into conscious awareness. Following this stage, we experience a loss of identity corresponding in scale to the trauma we just released.

Before we can understand what loss of identity is, we must ask: what is identity?

What is identity?

Our identity is who we are—or more, accurately, who we feel we are.

The distinction is important because, as a species, we’re not fully aware of who we are.

As a patriarchal society, our individuality has been subjected to six thousand years of shame-based conditioning to conform to societal ideals.

This conditioning—imposed through both external suppression and internal repression—is what psychiatrist R. D. Laing referred to in the 1960s in the title of his book, The Politics of Experience. In other words, in patriarchies, experience itself is politicised. He writes:

“Our capacity to think, except in the service of what we are dangerously deluded in supposing is our self-interest, and in conformity with common sense, is pitifully limited… What we call ‘normal’ is a product of repression, denial, splitting, projection, introjection, and other forms of destructive action on experience… The ‘normally’ alienated person… is taken to be sane.”

So, in one sense, loss of identity has already happened before we release trauma. Our real identity has been compromised by the imposition of what Laing refers to above as ‘normal’.

The ‘false self’

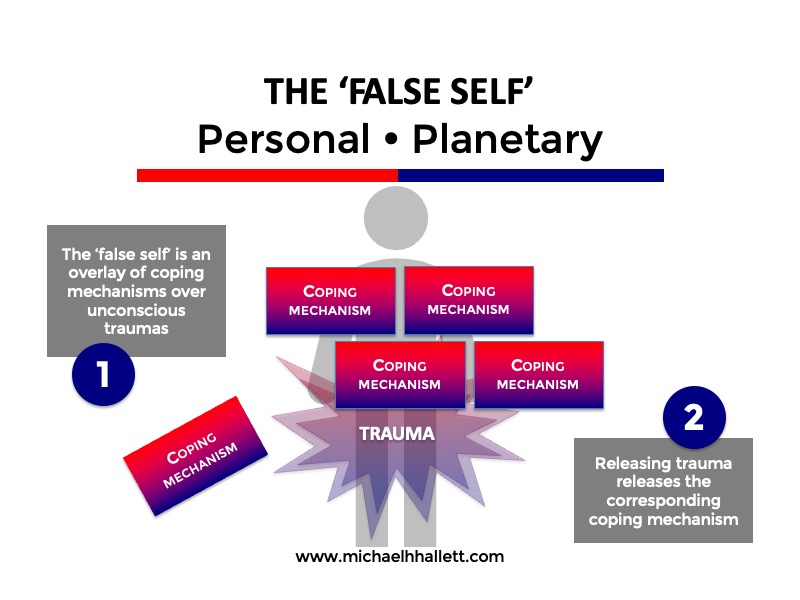

A more telling name for this abnormal identity we all have is the ‘false self’.

The concept of the ‘false self’ emerged in psychoanalysis in the 1960s. Known by a variety of terms (e.g., the ‘fake personality’), it’s attributed to Donald Winnicott.

Winnicott argues that we all have a true self—the part of us that feels safe, alive, and able to express ourselves spontaneously—and a false self, an emotionally frozen façade we present to the world to paper over our survival fears. The purpose of the false self is to keep us functioning (i.e., surviving) in a trauma-based society.

The false self can be envisaged as psychological blocks—Pink Floyd’s “bricks in the wall”—of coping mechanisms built on top of our traumatised self. Each trauma—each point of loss of self—manifests its own coping mechanism to counteract the loss.

The interplay of these true and false selves is what we think of as our personality.

In The Function of the Orgasm, early psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich describes this psychological wall in terms of ‘armouring’. He name-checks some of the destructive behaviours it causes:

“The character structure of modern man, who reproduces a six-thousand-year-old patriarchal authoritarian culture, is typified by… armouring against his inner nature and against the social misery which surrounds him. This… armouring is the basis of isolation… fear of responsibility, mystic longing, sexual misery, and neurotically impotent rebelliousness.”

Loss of identity

It is this armouring—the armour of the unconscious—that we penetrate when we recognise and release trauma.

When we release trauma, we experience a lightening of whatever emotion the trauma expressed itself through. For instance, it could be pain, grief, shame, guilt, or depression.

Secondly, the coping mechanism we used to deal with that trauma falls away.

For instance, I recently cleared a trauma around feeling worthless. I immediately noticed that my habit of checking news feeds multiple times a day stopped. I simply lost interest.

My guess is that, subconsciously, I was checking the news to see if something was going to pop up telling me I was worthy. That sounds stupid, but our coping mechanisms always obey a simple rule: they reflect in some way the pain that underlies them.

Our loss of identity from releasing trauma stems from these two shifts, one internal and one external. In combination, they leave us not quite sure of who we are. We may feel a sense of being in a vacuum for a little while.

If we’re not expecting it, this loss of identity can feel a little disorienting and deflating. We feel the emotional lightness from the released trauma. At the same time, we have a vague sense of not knowing who we are.

This is temporary. Releasing trauma is always beneficial. The less emotional bricks we must carry, the lighter our burden in life.

Next steps

For further resources on generational trauma, both free and paid, please click on this image.

Photo by Claudia Soraya on Unsplash