What are shame-based issues?

- 3 March 2017

- Posted by: Michael H Hallett

- Category: Cornerstones , Shame ,

Unconscious shame has given rise to a family of shame-based issues that all share a common denominator: the inability to discuss them. I’ve written about the origins of this shame in A brief history of shame. Here I discuss some of the ways our millennia-old unconscious shames blights modern lives.

Shame-based issues

Anytime you encounter an issue that someone would rather ‘sweep under the carpet’ you’re dealing with unconscious shame. We often lack the ability to verbalise what the issue is. In What is unconscious shame? I pointed out that our dictionary definitions of shame don’t include unconscious shame. We lack both the language to discuss shame and social permission to do so. This is because questioning what is shameful is also shameful.

In The Politics of Experience, psychologist R.D. Laing writes that, “What we call ‘normal’ is a product of repression, denial, splitting, projection, introjection and other forms of destructive action on experience”. These “forms of destructive action” are the basis of both our shame-based behaviours and our inability to discuss them.

“No one can begin to think, feel or act now except from the starting-point of their own alienation.”

— R.D. Laing

Laing’s quote highlights that shame affects how we “think, feel or act”—the whole of our lived experience. Laing goes on to say that, “Our behaviour is a function of our experience. If our experience is destroyed, our behaviour will be destructive”. The Italics are Laing’s, not mine.

Shame-based issues are the manifestation of that destructiveness. It can be directed at others, at the self, or even both. For highly sensitive people, shame can feel so overwhelming and humiliating that they would rather die than face it.

“Unwarranted sexual advances”

In 2014, 15-year-old Josie Herniman was found hanged in the woods near her home in Somerset. She had friends and a loving family. A Facebook photo shows a smiling teen snapping a selfie. There were allegations of bullying and “unwarranted sexual advances” the police were unable to substantiate.

The coroner ruled that Josie did not intend to kill herself. Yet Josie told a friend she had tried to take her life a year earlier. Two suicide attempts seem hardly accidental. The unproven allegations centred on emotions and sexuality, the exact sphere of unconscious shame.

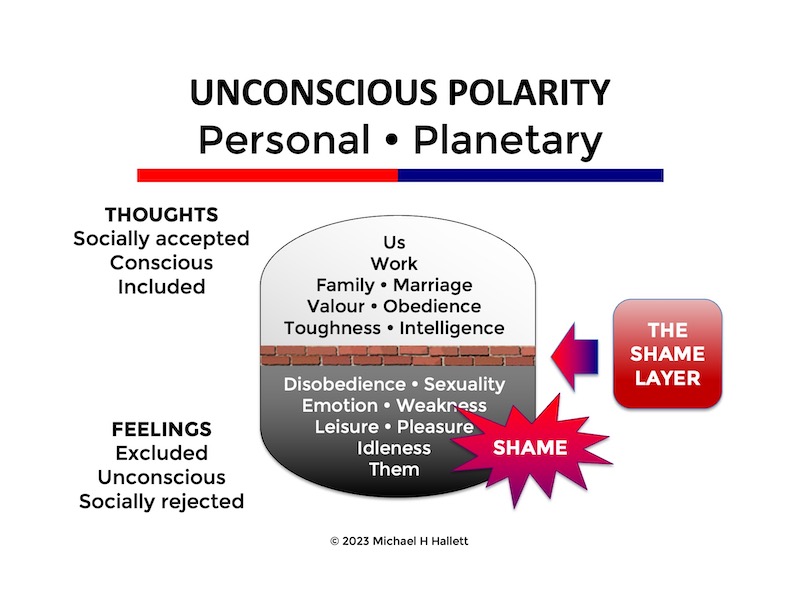

The following diagram shows how unconscious shame causes us to split our being into acceptable and unacceptable aspects. The mechanism for this—the horizontal line in the diagram—is called the ‘sexual-spiritual split’. It’s the dividing line between the consciously accepted ‘good’ part of us and the unconsciously rejected ‘bad’ part.

The following diagram shows how unconscious shame causes us to split our being into acceptable and unacceptable aspects. The mechanism for this—the horizontal line in the diagram—is called the ‘sexual-spiritual split’. It’s the dividing line between the consciously accepted ‘good’ part of us and the unconsciously rejected ‘bad’ part.

All the destructiveness of shame-based issues stems from this repressed, rejected ‘bad’ part of our psyche.

Not only does unconscious shame cause emotional pain, but it also prevents the natural release of that pain and makes it difficult to seek therapy or even discuss the issue. That’s because weakness—needing help—was historically taboo. It still remains so today, particularly for men. We bottle our pain and try to muddle through—unless we reach a point of overwhelm.

Not only does unconscious shame cause emotional pain, but it also prevents the natural release of that pain and makes it difficult to seek therapy or even discuss the issue. That’s because weakness—needing help—was historically taboo. It still remains so today, particularly for men. We bottle our pain and try to muddle through—unless we reach a point of overwhelm.

Was Josie’s death an accident—or the only way to cope with unbearable yet inadmissible pain?

Coping mechanisms

Carl Jung wrote that humanity’s task is to “make conscious that which presses upward from the unconscious”. The phrase “presses upward” highlights the emotional pressure that the unconscious exerts as it seeks our conscious attention so that we will heal it. (See Our lives are constant feedback loops.)

Shame-based issues are coping mechanisms to find release from this pressure. The more sensitive a person is, the more they are aware of their repressed femininity—and of our society’s unconscious shame of all things emotional and sexual.

However, because society does not recognise its own unconscious shame, we misunderstand these communications. Instead of listening to them we try to silence them either through making them go away (temporarily releasing the pressure) or obliterating them with a more intense life experience—drugs, alcohol, sex, eating, consumerism. These are all attempts at anaesthetizing “that which presses upward from the unconscious.”

Shame-based issues function principally on a similar basis to the fight-or-flight response. Some issues span multiple categories:

- Attacks upon the self (‘fight’)—anorexia, bulimia, self-harm, sexual dysfunction (e.g. masochistic practices)

- Attacks upon others (‘fight’)—sexual dysfunction (e.g. ‘rough sex’), honour-based violence, radicalisation

- Avoidance strategies (‘flight’)—over-eating, binge drinking, drugs, cigarettes, depersonalisation disorder, porn addiction, sexual dysfunction (e.g. unconsciously avoiding sex)

On this site I’ve written principally about the shame-based issues I have the most experience with, either personally or supporting others.

The shame cycle

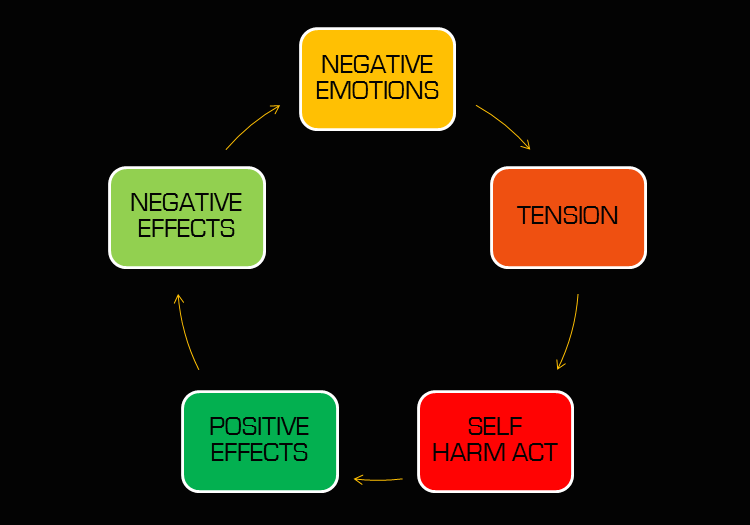

Many shame-based issues manifest on a cyclical basis, which gives rise to a cyclical coping mechanism: the shame cycle. This cycle of behaviour applies to a variety of issues such as self-harm, porn addiction, drugs, eating disorders and binge drinking.

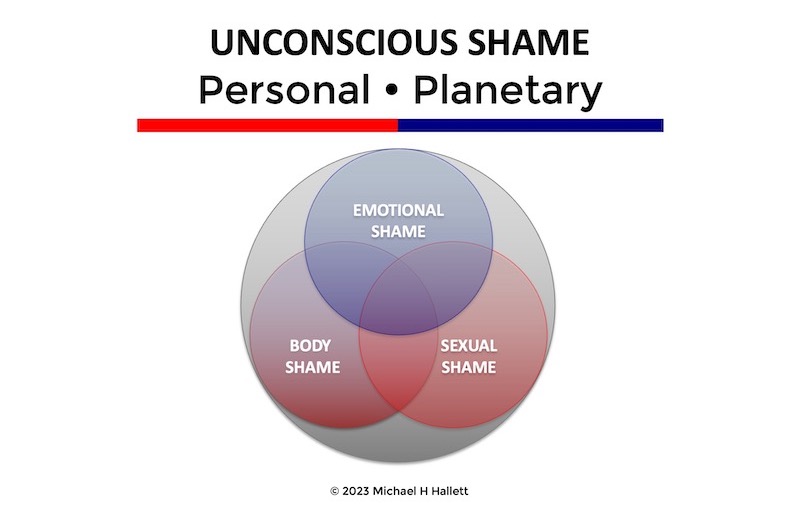

The starting point of the cycle is the reservoir of unconscious shame and negative self-beliefs, labelled ‘negative emotions’ above. As I wrote above, these centre on the emotions, the body and sexuality. It’s no coincidence that the coping mechanisms used to manage these distressing, shameful feelings centre on the same aspects of the self.

As long as we fail to recognise the unconscious shame underlying this epidemic of destructive behaviour, more and more people will tread the same tragic path as Josie Herniman.

Anxiety

Anxiety is the handmaiden of unconscious shame and accompanies all shame-based issues.

The need to repress our emotions and sexuality to avoid punishment automatically creates an anxiety that we’ll be exposed for failing to meet social expectations.

This anxiety develops during adolescence, unconsciously transmitted by parents, teachers and other social institutions. Psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich describes the mechanics of anxiety:

“The conflict that originally takes place between the child’s desires and the parents’ suppression of these desires later becomes the conflict between instinct and morality within the person.”

— Wilhelm Reich

R.D. Laing echoes this: “The Family’s function is to repress Eros… to induce a fear of failure… to promote a respect for ‘respectability’.” All of this induces anxiety. The level of anxiety we experience is directly related to our level of sensitivity: the higher the sensitivity, the higher the anxiety.

Next steps

For further resources on shame, both free and paid, please click on this image.

Photo by Ian Espinosa on Unsplash