What is the ‘false self’?

- 20 October 2020

- Posted by: Michael H Hallett

- Category: Cornerstones ,

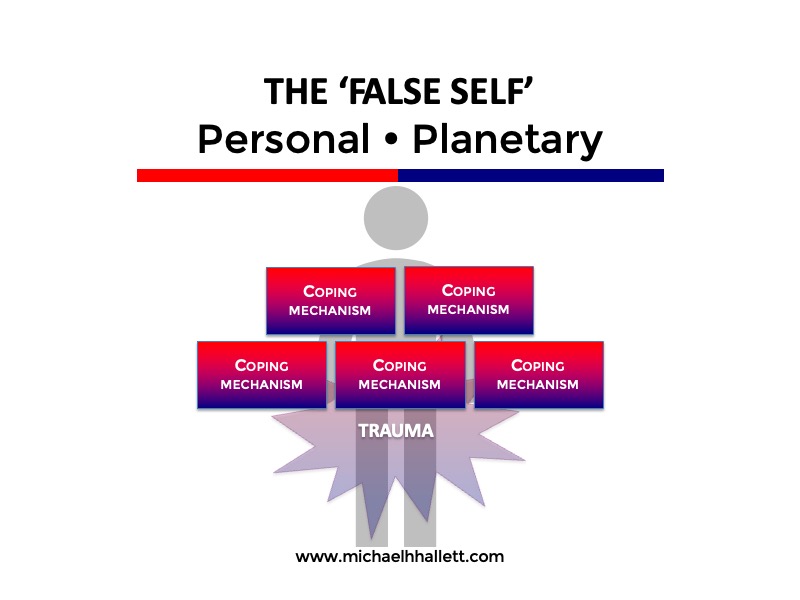

In blogs such as What is the unconscious?, What are shame-based issues? and How shame affects arrested development I describe the psychological legacy of patriarchy. Here I pull together various strands to describe some of the ways this legacy affects us. A major way is through the automatic, unconscious creation of a ‘false self’.

The false self is a psychological mask that reflects back to society only what society considers acceptable. That’s why I’ve chosen this beautiful image of a reflective mask by Alex Iby.

The existence of a false self implies the existence of a complementary ‘true self’. The true self is also known as the ‘vulnerable self’, which gives you a sense of its characteristics.

The false self is a key component of what I call the Patriarchal Operating System, the acquisitive, consumptive and destructive psychological model that’s crippling humanity and the planet.

What is the ‘false self’?

The concept of the false self emerged in psychoanalysis in the 1960s. Known by a variety of terms (e.g. the ‘fake personality’), it’s attributed to Donald Winnicott.

Winnicott argues that we all have a true self—the part of us that feels safe, alive and able to express ourselves spontaneously—and a false self, an emotionally frozen façade we present to the world to paper over our survival fears. The purpose of the false self is to keep us functioning in a trauma-based society.

Winnicott attributes the false self to ‘not good enough’ parenting. Due to excessive projection of parental fears and anxieties, the child replaces its natural behaviours with artificial ones to elicit a less painful response from its carers:

Other people’s expectations can become of overriding importance, overlaying or contradicting the original sense of self, the one connected to the very roots of one’s being… through this false self, the infant builds up a false set of relationships, and by means of introjections even attains a show of being real.

Our whole society is “a show of being real.”

Parental anxiety

In The History of Childhood, Lloyd DeMause writes that when parents struggle, it’s “the child’s function to reduce the adult’s pressing anxieties; the child acts as the adult’s defence.”

The parents, of course, are trying to raise the child through the screen of their own false self. DeMause argues that ‘good enough’ parenting comes from “the ability of successive generations of parents to regress to the psychic age of their children and work through the anxieties of that age.”

Patriarchal societies function by shaming, suppressing and repressing the feminine aspects of being human—the emotions, sexuality and bodily functions.

Child rearing forces parents to confront these taboos. The presence of their own emotionally rigid false self reduces the parents’ ability to meet the child’s needs. This anxiety is transmitted to the child, which then represses those same aspects of its being to survive.

This traumatic mechanism perpetuates anti-feminine, anti-child and anti-sex cultural beliefs and practices. DeMause: “Child-rearing practices… are the very condition for the transmission and development of all other cultural elements.”

‘Normal’

Repressing its natural instincts causes the child’s psyche to fragment into accepted and rejected elements. In The Journey Toward Complete Recovery, Michael Picucci terms this psychic chasm the ‘sexual-spiritual split’.

We bury the rejected parts under a layer of unconscious shame and, both as individuals and as a society, pretend those parts don’t exist.

In The Politics of Experience psychiatrist R.D. Laing writes that, “What we call ‘normal’ is a product of repression, denial, splitting, projection, introjection and other forms of destructive action on experience.”

Because we all have a false self, fake emotional relationships and exchanges become normalised and unconscious.

Examples of the false self

An example of this is that couples unconsciously hide the deepest parts of their true selves—their sexual and emotional wounds—from their partners for fear of rejection and abandonment. The result is an emotional ‘hole’ at the core of many relationships.

The victimizer/victim dynamic whereby we all victimise each other to try to meet our needs is a key example. We unconsciously allow ourselves to be victimized in many aspects of our lives. In return, we victimize others (e.g., men demanding sex from their wives) to feel we have at least some level of satisfaction.

Other examples of ‘false self’ coping mechanisms are a fear of change and being a control freak. Panic (or paralysis) in the face of change is an adult reaction to childhood trauma that’s been perpetuated through arrested development.

The false self is what’s left over when we’ve finished repressing the parts of ourselves that we fear will get us in trouble.

The false self is what’s left over when we’ve finished repressing the parts of ourselves that we fear will get us in trouble. The more we repress, the more lifeless our false self—and our life experience—is.

Introvert v extrovert

The false self can be introverted or extroverted—indeed, I suspect it’s the source of this categorisation. Some people compensate for feelings of insecurity by over-projecting themselves onto their surroundings, seeking safety through control and domination of their environment.

Others do the opposite, withdrawing behind a wall of meekness due to fears of being unable to compete with or control their surroundings. By keeping out of the limelight they hope to sneak through life without attracting attention.

Introvert versus extrovert is the false self’s version of fight or flight.

In both cases, the false self is underpinned by emotional unavailability—showing up physically and mentally, but not emotionally—and by a lack of responsibility for our feelings.

Anaesthesia and blame

When we hurt we look for two things: something to lessen or stop the pain, and someone—anyone—to blame.

The result is a society founded on the twin pillars of anaesthesia and blame. We devote our whole lives to stopping ourselves feeling bad—through money, love, sex, food, shopping, alcohol, drugs, music, Netflix… whatever. Society’s attitude to alcohol is entirely based on rewarding ourselves with numbness.

Whenever we are forced to confront the pain of our survival fears we react by blaming someone else, often expelling them from our lives in the hope this will stop the pain.

It doesn’t, because the pain is inside us.

Deconstructing the false self

Richard Schwartz, creator of the Internal Family System model for healing trauma, refers to the components of the false self as ‘parts’. These parts are frozen in time. They are parts of ourselves that are simply trying to protect us from the trauma that gave rise to them. Healing consists of retrieving and reassigning these parts. This means bringing them into the present them giving them new, healthy functions.

The hardest thing about the false self is accepting that we have one—and accepting responsibility for deconstructing it. Normally this only happens due to the emotional pressure of a relationship breakdown or other significant personal loss.

It’s very disconcerting to discover that the person you think is ‘you’ is actually comprised of a bunch of coping mechanisms designed to minimise pain. In the need to ease your pain, these mechanisms will willingly inflict pain on others.

Pain, therefore, is the indicator we use to identify when the false self is in play and the roadmap of what needs to be healed.

Whenever we have an experience to which we react with pain, we have a choice. Either we turn to anaesthesia and blame, looking to distance ourselves from the experience—or we go towards it.

This means sitting with the pain, feeling it, accepting it—even welcoming it. There’s no way out of the false self other than through the pain that created it.

Releasing shame

Everything that’s in pain is in shame. So consciously releasing shame allows us to uncover the pieces of the false self. Be aware that the closer you are to unearthing these fragments, the more they will affect you.

Releasing deep shame and the coping mechanisms of the false self is an unnerving experience. The person we thought we were melts inside us and a new, healthier person emerges—usually accompanied by turbulence in our lives. This can be the end of friendships or relationships, job losses or financial failure.

Life can feel like it’s completely out of control—yet, the further along we go, the more we become aware of the intelligence and grace of the process. It is truly a controlled demolition of the false self, ultimately delivering us into a life where only our true self—loving, loved, safe and spontaneous—exists.

Photo by Alex Iby on Unsplash