The mother wound – “The dreadful has already happened”

- 22 October 2020

- Posted by: Michael H Hallett

- Category: Cornerstones , Mother wound ,

In a lecture a few years after the atomic bomb ended World War II, German philosopher Martin Heidegger asserted that “the dreadful has already happened.” The lecture, titled ‘The Thing’, was delivered to the Bayerischen Akademie der Schönen Kunste [Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts]. Translated by Albert Hofstadter, it was published in 1971 in a collection of Heidegger’s work called Poetry Language Thought.

The overarching theme of ‘The Thing’ is that if humanity can build a weapon with the potential to annihilate all life on earth, then something long ago went seriously—perhaps fatally—wrong with our connection to the very essence of existence:

“Man stares at what the explosion of the atom bomb could bring with it. He does not see that the atom bomb and its explosion are the mere final emission of what has long since taken place, has already happened… What is this helpless anxiety waiting for, if the terrible has already happened?”

The dreadful

The German phrase das Schreckliche translates as either ‘the dreadful’ or ‘the terrible’. Hofstadter used the latter, but the quote survives with the somehow more threatening adjective ‘dreadful’; terrorism has dulled our sensitivity to terror and the terrible.

What is the dreadful? Heidegger begins by noting that other products of modern technology, including jet planes and film cameras, have annihilated distance:

“All distances in time and space are shrinking. Man now reaches overnight, by plane, places which formerly took weeks and months of travel… Yet the frantic abolition of all distances brings no nearness; for nearness does not consist in shortness of distance.”

Nearness is Heidegger’s shorthand for a full connection to the essence of life. Its absence is a horror so awful we haven’t allowed ourselves to grasp it.

The paradox of the remoteness of nearness is the spine of ‘The Thing’. It is the shadow cast by the dreadful, which cannot otherwise be seen—like the Greek Medusa whose appearance was so hideous that anyone who saw her turned to stone.

The thing

Heidegger approaches his topic through the lens of a specific thing—a hand-made ceramic jug, a seemingly ordinary object he later reveals to have sacred properties. He writes that we pursue nearness through objects—things—but what is a ‘thing’?

Heidegger excavates the layers of the jug’s ‘thingness’: its physical makeup—ceramic base and sides; its function—holding and pouring; its production and producer—the kiln, the potter; the idea of its specific production; the formless concept of a vessel.

Which of these is the thing—and where does the lack of nearness abide?

To answer this, Heidegger turns to the jug’s use: “There is water, there is wine to drink.” The jug holds and pours life-giving water, and wine that raises our spirits and which the ancients—when the dreadful was still in its infancy—poured in gratitude to whatever gods they recognised:

“In the water of the spring there abides the marriage of sky and earth. They abide in the wine that the fruit of the vine provides, in which the nourishment of the earth and the sun of the sky are betrothed to each other… The gift of the pour as oblation is the authentic gift.”

Science

But science, Heidegger writes, has a “compulsion to relinquish the jug filled with wine and to put in its place a cavity in which a fluid expands. Science makes the jug-thing into something negligible…”

Our reductionist worldview isn’t the problem. It’s a manifestation, a coping mechanism arising from a problem that occurred long ago. When you’re disconnected from life, you inevitably invent a means of explaining—or seeming to explain—life that excludes this disconnection.

Science is a wonderful tool. We come into proximity with ever more useful gadgets, yet at the same time the lack of nearness—genuine emotional connection and, transmitted through it, nurturing—is increasingly destroying us.

“Only for this reason can pouring become, as soon as its essence atrophies, a mere filling up and emptying out, until it finally degenerates into the ordinary serving of drinks.”

The dreadful is the atrophying of our connection to the essence of life. We fill up and empty out, numbed by unconscious consumption, failing to recognise that genuine nurturing (“the nourishment of the earth and the sun”) is absent.

Anxiety and intimacy

“What is this helpless anxiety waiting for, if the terrible has already happened?” Heidegger asks. We wait with growing anxiety for the full impact of the dreadful, like a slow-motion nuclear bomb whose mushroom cloud blast has taken 6,000 years to reach us.

We are drowning in disconnection in a perfect storm of social and economic problems, declining physical and mental health, and unsustainable consumerism—all stemming from the lack of nearness that prevents us from valuing life, each other, and the planet.

Heidegger’s lecture fails to pinpoint the dreadful; only that it’s already happened. The nearness that he seeks, that he identifies as missing, does not exist in a dimension of thinking. It exists in a dimension of feeling.

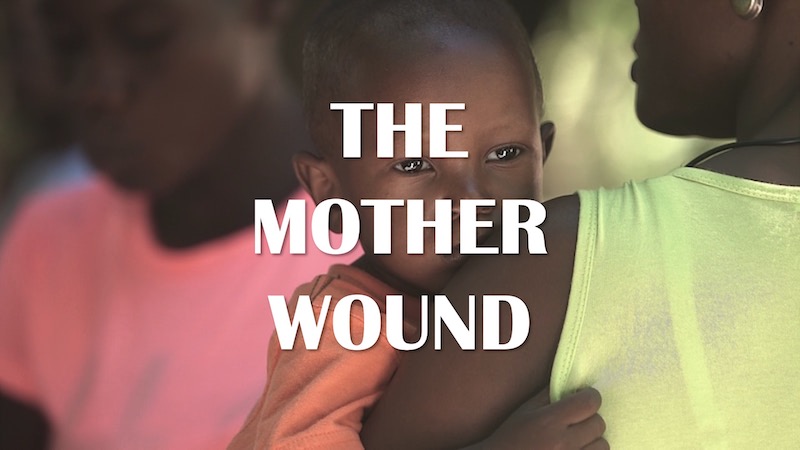

If we translate the technical, measurable word ‘nearness’ into a feeling word, that word is ‘intimacy.’ We lack genuine intimacy with others, with ourselves, with life itself. We transmit that lack from generation to generation through a damaged mother-child bond.

This is called the mother wound.

Next steps

For further resources on the mother wound, both free and paid, please click on this image.

Photo by Johnny Chen on Unsplash

This is a valid interpretation of Heidegger’s ‘The dreadful has already happened’. There’s another way of seeing it. The dreadful is the loss of the inner self; the esoteric side of our nature – the part of the psychological iceberg hidden under the surface. It was Whitehead who said we’ve all been soul murdered and don’t realise it. The Christ light in us has been extinguished by a total immersion in carnality. Spirit has been allowed to wither and die. The notion of Christ taught by the Christian churches is the superficial Christ that has no influence over the conduct of individuals or congregations. Luke 17:21 says that the Kingdom is nowhere other than within each of us. When I was raised as a Catholic, that neo-Fascist organization went out of its way to kill that inner Christos in me. It failed because I jacked up.

I rebelled and excommunicated myself. I listened to an inner voice (conscience) that told me I was dealing with soul murderers. The dreadful nearly happened with me. But I know of 1.2 billion people who’e had it happen to them. The good news is that after seventeen centuries of crimes against humanity, that arrogant authority is falling apart at the seams. The Infinite is never in a hurry to see justice done.

Thank you so much Laurie. Not familiar with Whitehead but “soul murdered” is such an apt phrase.

Completely agree re Luke 17:21, it points directly to the heart of the matter.

“The Infinite is never in a hurry to see justice done.” Poetic truth!!