Leonardo Da Vinci’s drawing, the Vitruvian Man, has always fascinated me. Drawn around 1490, Da Vinci’s drawing is named after the Roman architect Vetruvius. He not only stipulated the physical proportions of the ‘ideal man’ but also hypothesised that such a figure would fit inside both square and circle.

The complex geometry of the Vitruvian Man hints at the even more complex geometry that underlies all of creation. That is what makes Da Vinci’s drawing so fascinating. It suggests perfect proportions in the unseen dimensions of life, not just the height, width and depth of the physical world.

Vitruvian Man

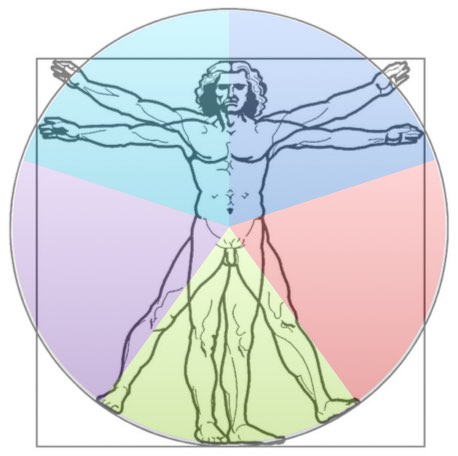

These unseen dimensions include our mental, emotional, spiritual and sexual selves. Recognising these five dimensions and adding them to the Vitruvian Man creates a representation that reminds me of those foil-wrapped cheese wedges from La Vache qui rit:

We cannot be ideal humans until we are perfected in our mental, emotional, spiritual and sexual aspects just as much as in our physical bodies. And we cannot perfect those aspects until we unashamedly embrace them.

We cannot be ideal humans until we are perfected in our mental, emotional, spiritual and sexual aspects just as much as in our physical bodies. And we cannot perfect those aspects until we unashamedly embrace them.

Society has historically limited emotional and sexual expression to a very narrow spectrum of approved behaviour. This has created an unconscious shame of our emotions and sexuality that prevents us from expressing them healthily.

Our repressed emotions express themselves in anxiety, panic attacks, self-harm and blaming others whenever we feel hurt. Our repressed sexuality shows itself in phobias, destructive affairs, erectile dysfunction, premature ejaculation and porn addiction.

Triggers

We can’t control these behaviours because they are unconscious responses to emotional triggers. Carl Jung wrote, “Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate”. Shame is the invisible barrier that prevents access to our unconscious. Thus it prevents us from fully embodying the lofty idealism of the Vitruvian Man.

The Vitruvian Man suggests to me a superimposition of the crucified Christ and the risen Christ.

In The Clementine Recognitions, an early Christian work, the Apostle Paul connects Christ with the term ‘ideal man’. Though Da Vinci drew him in a Christian milieu, he’s a universal figure. Gerald Massey argues in The Natural Genesis that the Christ who dies and is resurrected after three days in the underworld has antecedents stretching back through the Greek mystery schools to the Egyptian Book of the Dead.

Whether we believe in death and resurrection in a religious, spiritual or any other form or not, we all experience painful mini-deaths and resurrections as we strive to perfect our own lives. The immaculate geometry of Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man spurs us towards an idealism that can only be achieved without shame.

Next steps

For further resources on shame, both free and paid, please click on this image.

Image: Leonardo Da Vinci, The Vitruvian Man, 1492 (public domain)