Childhood innocence – concealing the mother wound

- 11 August 2023

- Posted by: Michael H Hallett

- Category: Cornerstones , Mother wound ,

I recently uncovered some trauma around the idea of childhood innocence. This surprised me, as I’d never really thought about the concept. I didn’t realise that by pressing into it I’d encounter a classic, shame-based can of worms. And, beneath it, the mother wound—humanity’s single point of failure.

What is childhood innocence?

I often ask ‘what is’ something in my blogs, so I immediately did some research.

A Harvard Gazette article quotes Professor Robin Bernstein as saying that the idea “only became common sense in the United States in the early 19th century.” However, it came with a racial caveat: “It was not just any childhood, it was specifically white childhood that was entangled with innocence.” Entangled. Interesting. Bernstein notes that African Americans adopted the idea a century later.

The racial divide Bernstein identifies flagged that there was another divide in play: wealth. Childhood innocence is a white, affluent, 19th century re-imagining of adolescence as a mythical time-space where children are protected from the ‘realities of life’.

These include work, violence, parenting, drudgery, social inequality, death, and sex. Instead, children are spoon-fed fables such as Father Christmas, Disney films, and sexless creatures like the Minions.

The mother wound

Yet childhood innocence runs deeper than this. The white, 19th century version is a veneer over a deeper pattern affecting all races—it covers up what lies beneath: the mother wound, the bleeding rupture at the core of humanity.

In What is the mother wound? I describe the profound physiological changes that happened to humanity some 6,000 years ago due to long-term drought, desertification, and famine in the Sahara, Middle East, Arabia and great swathes of Central Asia.

“A passive indifference to the needs or pain of others manifested itself, and hunger, feeding of the self, became their all-consuming passion… The very old and young were abandoned to die. Brothers stole food from sisters, and husbands left wives and babies to fend for themselves. While the maternal-infant bond endured the longest, eventually mothers abandoned their weakened infants and children.”

— James DeMeo, Saharasia

Breaking the mother-child bond broke our connection with the cosmos, with nature, with the breast, and with our own bodies. These breakages have never been fully healed and explain the wanton destructiveness of what we naively call ‘civilization’.

At its heart, the mother wound causes a failure of nurturing. This prevents our inner child—the pure, playful, joyful, fully connected part of ourselves—from developing into our adult self. This lost inner child is at the heart of childhood innocence.

So, who invented childhood innocence—children or adults?

“Closer approaches”

Lloyd deMause describes the history of childhood as “a series of closer approaches between adult and child.” These approaches have been driven by the emotional sensitivity—or lack of it—of parents:

“A hundred generations of mothers tied up their infants in swaddling bands and impassively watched them scream in protest because they lacked the psychic mechanism necessary to empathize with them.”

— Lloyd deMause, ed., The History of Childhood

DeMause writes that, historically, children were used as “a ‘toilet’ for adult projections” and that, of “over two thousand references to children listed in the Complete Concordance to the Bible… not a single one… reveals any empathy.”

Parents were emotionally so far removed from their children that the failure of nurturing imparted by the mother wound was ‘hiding in plain sight.’ It passed completely unnoticed due to the parents’ insensitivity.

Renaissance

According to deMause, this changed in the 15th and 16th centuries during the Renaissance, when “advice to temper childhood beatings began in earnest.” (White European history, yet it’s the only one we have. Few records of the lives of children of any race survive.)

With anti-child violence reducing, the next battleground was bodily functions: “the struggles between parent and child for control in infancy of urine and faeces is an eighteenth-century invention.”

Notice the pattern: 15th/16th centuries, violence; 18th century, bodily functions; 19th century, childhood innocence. Each shift driven by the parents’ slowly increasing sensitivity.

With the advent of the white middle class—I’m winging this a bit, but the important thing is the pattern, not the detail—rising living standards led to changes that allowed, in deMause’s terminology, another ‘closer approach.’ Children started to have their own bedrooms and no longer witnessed their parents’ conjugal relations.

“Troublesome activities”

At Home, Bill Bryson’s history of private life, fails to pinpoint this seismic moment.

He relates a 17th century account of two girls, one aged 16, sleeping “fundamentally naked” on a truckle bed (a low wheeled bed beneath their parents’ bed). Bryson goes on to recount that by the 19th century, bedrooms were places of dread because of “that most troublesome of activities, sex.”

This was a time of extreme fear of sex that manifested in the onanism (masturbation phobia) craze, as well as female hysteria leading to the invention of the vibrator to relieve doctors of the onerous task of inducing orgasms in frigid women.

Sex was excommunicated from the houses of the affluent and morally upright. In modern terminology, it was outsourced. In The French Lieutenant’s Woman, John Fowles writes that one house in every 60 in Victorian London was a brothel.

Children were locked into their own rooms at night and became ignorant of the ‘facts of life’. (It later fell to the birds and the bees to impart the dark secrets of reproduction.) Like all the traits of the well-to-do, this practice was eagerly adopted by those of lower social status as soon as they could afford it.

Caught up in the titillating details of Victorian sexual prudery, Bryson notes the before and after moments but doesn’t pin down either the shift or its importance. This little elision is symptomatic of the wider issue: no one wants to glimpse the mother wound.

The invention of childhood innocence

Why did all this happen? What problem could only be solved by the concept of childhood innocence? Like all preceding ‘closer approaches’, it’s about the parents, not the children. Childhood innocence was invented by the parents for the parents.

DeMause writes that “It is the child’s function to reduce the adult’s pressing anxieties; the child acts as the adult’s defence.” What anxieties? What needed to be defended against?

Is it a coincidence that childhood innocence appeared at the same time that (a) adults became chronically ashamed of sex and (b) wealthy enough to afford children’s bedrooms?

One manifestation of sexual shame—still prevalent today—is a fear of being seen engaging in any kind of sexual activity. Expelling children from truckle beds is an obvious response to the horror of one’s own sexual nature that emerged in the 19th century.

A generation of children ignorant of the facts of life created a knowledge gap that had to be filled somehow when those children became adults.

A sexless space

The need for the parent to become sexually uneducated—to avoid the growing pain of their own shamed and repressed sexuality—drives the need for a sexless space of innocence that the parents can fondly bask in as a fake memory.

The inner child is the emotionally stagnant child whose healthy development, damaged at conception by the mother wound, is further hampered by deliberate separation from the natural world.

This includes not only sex and death but from anything on the dark side of the life cycle—killing animals, gutting fish, rats, mice, spiders, vermin, dirt of all kinds (physical and moral) which, as Bryson does inform us, the Victorians became preoccupied and petrified by.

Yet beneath the issue of sexual ignorance (which is to say, life ignorance) lurks something deeper—the looming iceberg of the mother wound as it smashes its way towards the surface of humanity’s collective psyche.

Childhood ignorance was unconsciously created to ward off humanity’s deepest, darkest, and most troublesome fact of life: the mother wound.

Clinging to childhood innocence

Once childhood innocence has been created, parents can wallow in the fantasy that their own childhood was innocent—despite all evidence to the contrary.

The BBC show The Repair Shop regularly features people getting some heirloom repaired that reminds them of their parents, often their father. They tearfully recall their childhood innocence. Yet when Dom Chinea softly asks, “What was he like?” the details often turn out to be a workaholic father who effectively abandoned his family.

My mother clung to her own childhood innocence in her love for Thomas Hood’s ode to childhood idyll, ‘I Remember, I Remember’—yet the reality of her upbringing was trauma, betrayal, abandonment, and fleeing the Nazis.

Childhood innocence was created to protect parents from two unbearable truths. Firstly, that they received no genuine emotional nurturing. Secondly, that they’re incapable of providing genuine emotional nurturing to their own children for the simple reason they don’t know what it is. They don’t even know it exists; how radically different it is.

The reality that childhood innocence protects adults and children alike from is the mother wound. It’s time, in the Biblical phrase, “to set aside childish things.”

Next steps

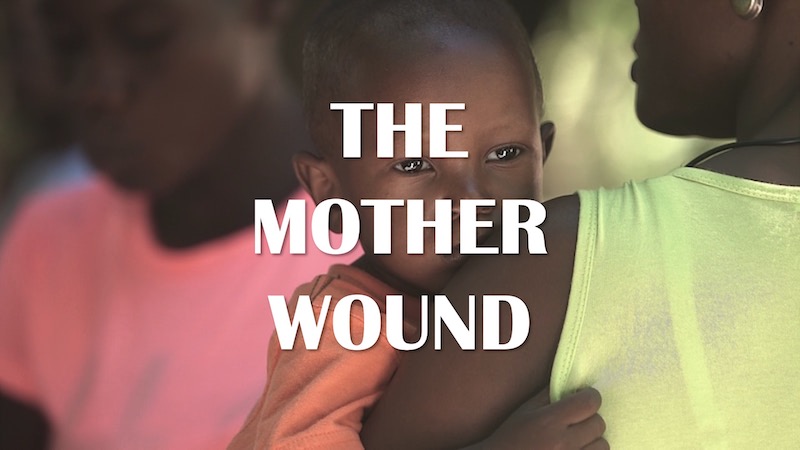

For further resources on the mother wound, both free and paid, please click on this image.

Image generated using Fotor AI