The end of the real-life Monopoly game

- 10 June 2017

- Posted by: Michael H Hallett

- Category: Emotional principles ,

The kitchen is filling up. It was deserted for a while but they’re drifting in now, in growing numbers, their faces blank with shock or denial. They’re looking for a cup of tea and a Jaffa cake. The cupboards, however, are bare. Someone finds an empty biscuit packet. A few crumbs spill onto the clear, shiny bench. Everyone stares at them. Everyone’s thinking the same thing. At some point a fight will break out and no one will stop it. It’s the end of the real-life Monopoly game.

If you want to know where the economy is headed, play Monopoly. Get as many players as you can and—please, this is important—make sure you play to the end. The game will begin with light-hearted bonhomie as people land on vacant squares, spend their allotted cash and snap up properties. (Already, by buying property, you’re ahead of many of the punters in the real-life Monopoly game.)

One-way street

As the game progresses, the mood darkens. The less competitive players resign themselves to an early exit while the more competitive ones size up their rivals and develop their strategies. Some players’ portfolios expand; others contract. It’s generally a one-way street. As the game proceeds, the smallholders and players with mid-sized portfolios gradually get squeezed out. Off to the kitchen they trot. First one in puts on the kettle.

That leaves the big boys—who, of course, might be girls but they must behave like boys (in the worst sense of the word) to survive. There’s no chit-chat now. Eyes glint as they follow the roll of each dice. Larger sums change hands with each turn; having sufficient liquid assets is essential. Eventually only the ‘winner’ remains—invariably suffering from emotional burnout—while the remainder leave in some sort of funk.

Market capitalist economies operate on exactly the same principle and we’re now at the stage where the small and mid-sized players are dropping out. The markers are all there. Homelessness is up, as is—significantly—the number of people who are in work but homeless. Next in line are the people in work but floundering.

Household debt is accumulating. They’re living on payday loans and by shuffling credit card balances. The interest is a shark that will rise up and—unless anxiety gets them first—drag them under. The payday lenders will shrug and mutter that it’s the system.

Always check for assumptions

Ah, the system. There seems to be an on-going assumption that because market capitalism delivered an economic boom in the second half of the 20th century, it would do so again in the first half of the 21st. All of the indicators suggest otherwise. Pay levels for senior executives are soaring while those beneath suffer. The wealthy are increasingly able to tilt the game in their favour. It’s the Monopoly game playing out, the widening crack between the haves and have-nots.

In fairness to those who cling to this assumption, no viable alternatives have yet been suggested. The first thing is to understand what a new system must do to address the situation.

The fundamental problem with market capitalism is that it places no structural value on wellbeing

The fundamental problem with market capitalism is that it places no structural value on wellbeing. It shuffles money around according to the skill, luck and starting position of the players but doesn’t care about the cost to physical and mental health.

As a result it creates an emotionally toxic society. Everyone is forced to trample over everyone else simply to survive and ends up psychologically ill, regardless of whether they become destitute—or utterly heartless to ensure that they stay in the game till the bitter end. It’s the only way they can keep out of that unseemly fight in the kitchen over the Jaffa cake crumbs.

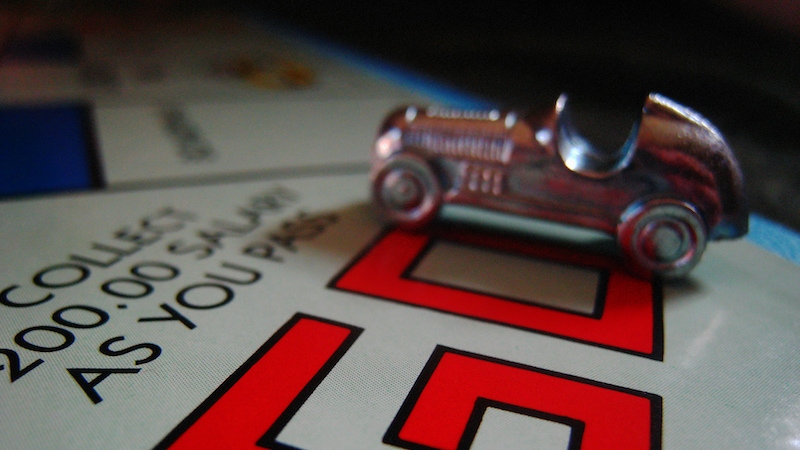

Image: Go by Bill Selak on Flickr. Cropped to 16:9.